Excess Fluid Volume is a major complication seen in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis, often linked to portal hypertension and impaired hepatic function. In the case of Mr. K., a 58-year-old retired factory worker with a history of chronic alcohol use and untreated hepatitis C, the development of ascites, peripheral edema, and breathlessness highlights the seriousness of Excess Fluid Volume Nursing Diagnosis. His condition illustrates how long-standing liver injury progresses to decompensated cirrhosis, where the liver can no longer regulate fluid balance effectively.

This nursing diagnosis is critical because fluid overload in cirrhotic patients is not only uncomfortable but also life-threatening. Ascites can compromise breathing, impair mobility, and contribute to malnutrition, while peripheral edema affects daily activities and overall quality of life. In severe cases, uncontrolled fluid retention may require repeated paracentesis or indicate worsening prognosis. Addressing Fluid Volume Excess in liver cirrhosis nursing diagnosis helps nurses set realistic goals, plan individualized care, and prevent complications such as infection, hepatorenal syndrome, or worsening hepatic encephalopathy.

The nursing process provides a structured framework to deliver evidence-based care in such complex conditions. By following its five steps—assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation—nurses can holistically manage Mr. K.’s needs. This care plan will outline how to apply the nursing process to his case, with interventions targeting fluid management, patient comfort, education, and ongoing monitoring. The goal is not only to reduce fluid overload but also to enhance functional capacity, improve quality of life, and support long-term disease management.

Comprehensive Assessment of the Patient with Cirrhosis

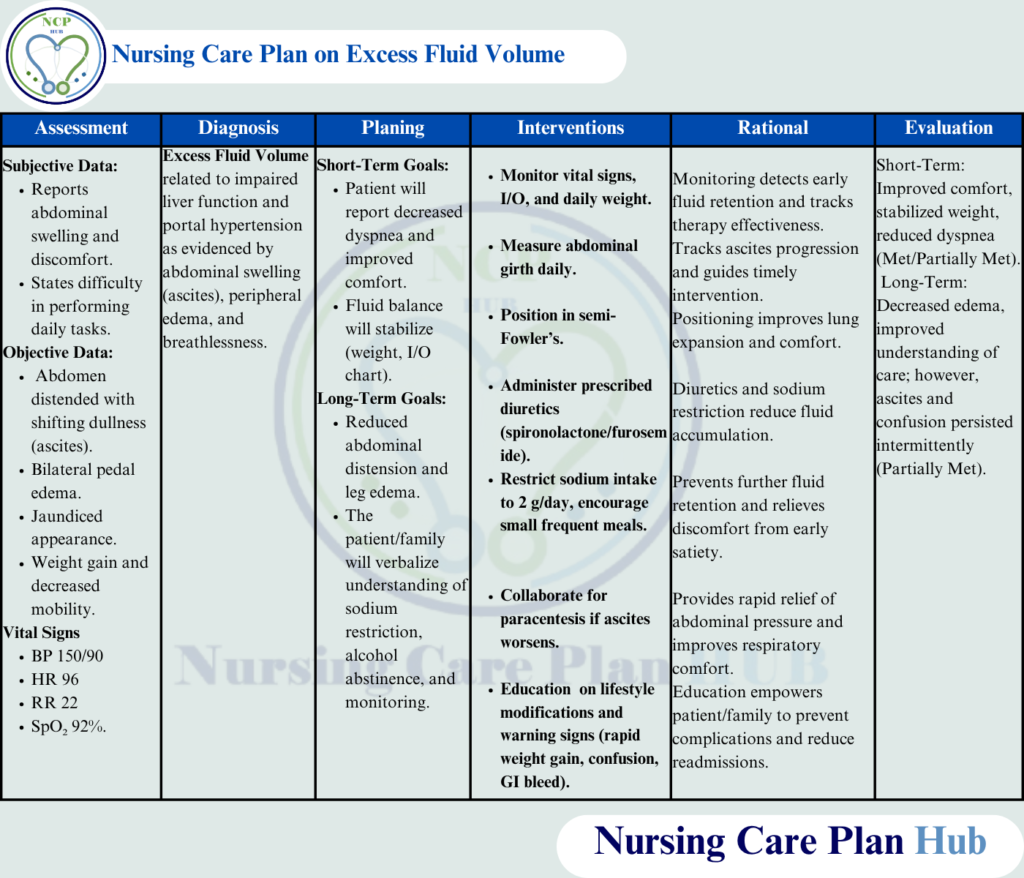

A thorough assessment is essential in understanding the extent of Excess Fluid Volume in patients with liver cirrhosis. Mr. K., a 58-year-old male with a sedentary lifestyle and history of heavy alcohol use, presents with multiple indicators of decompensated hepatic function and fluid overload.

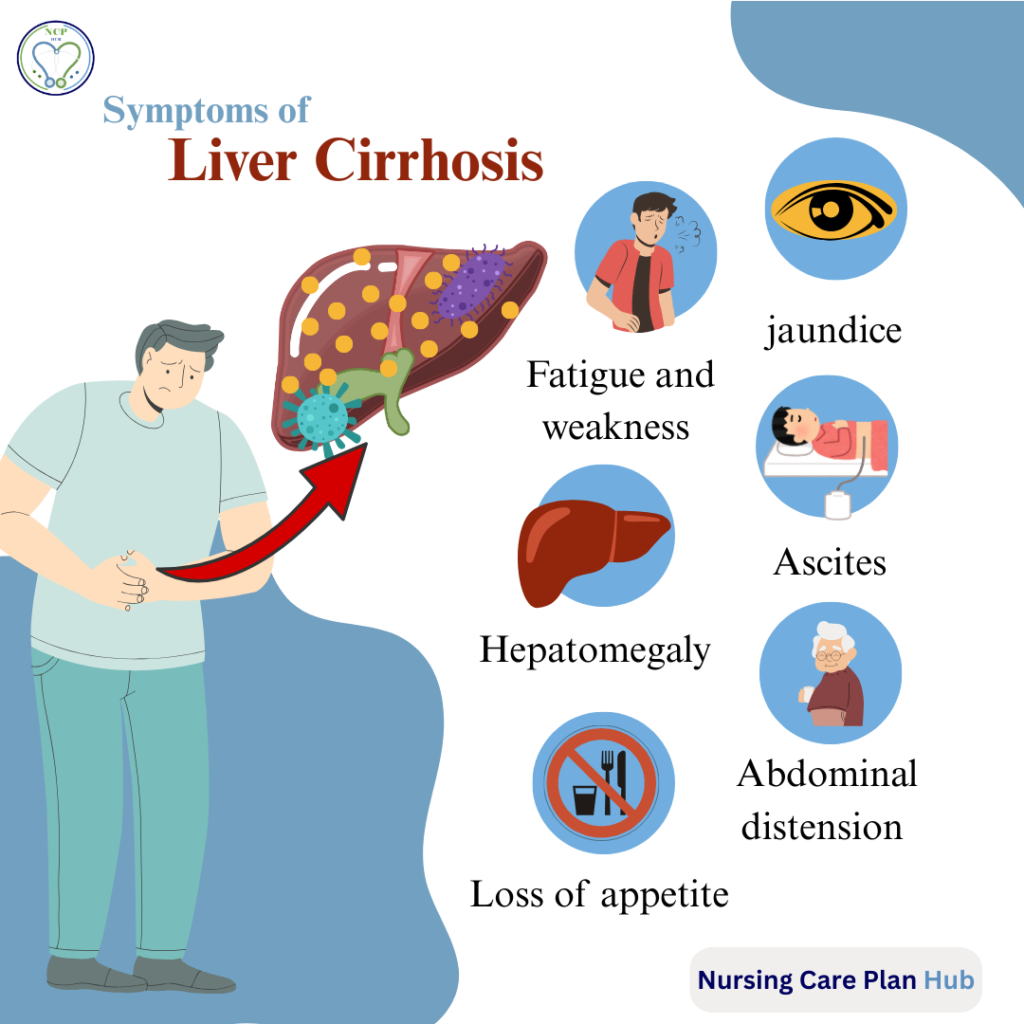

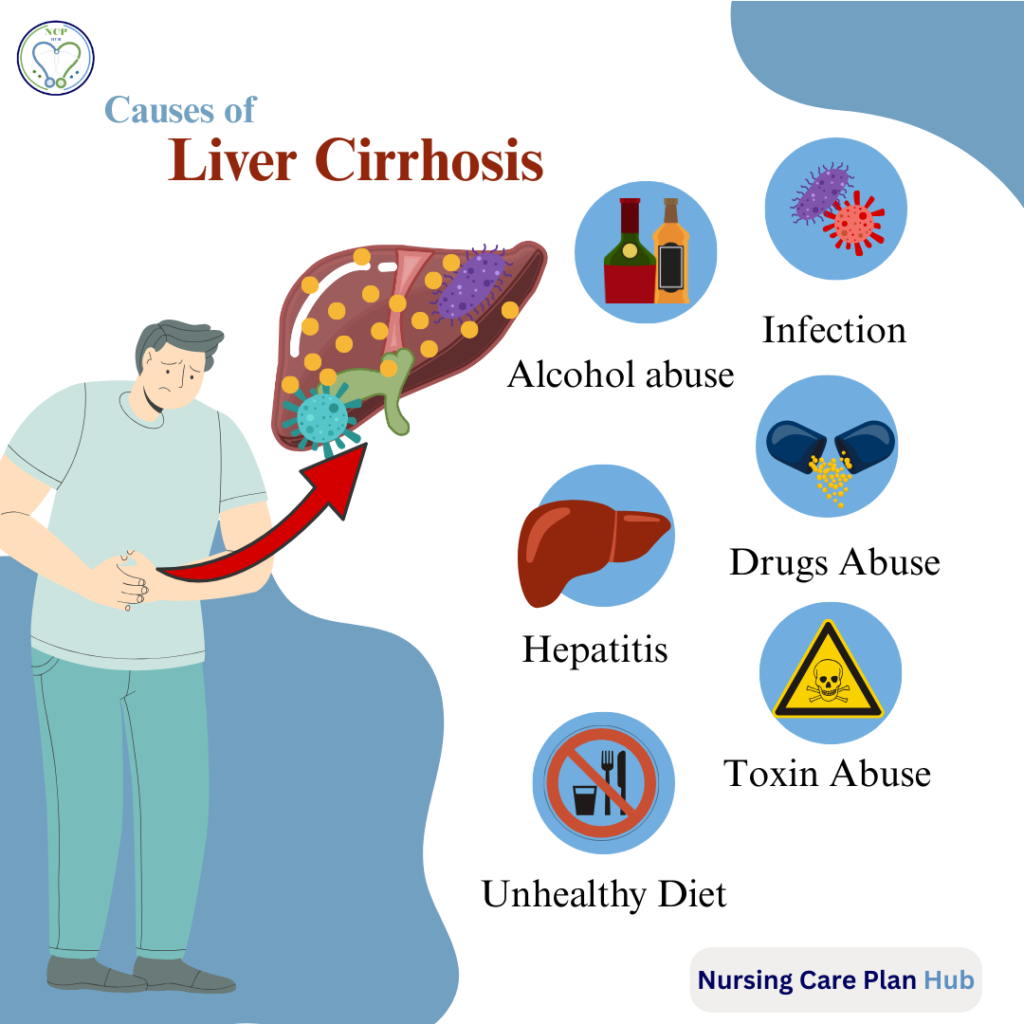

History: Mr. K. has a known history of hepatitis C (diagnosed 10 years ago but untreated) and hypertension controlled with medication. He consumed alcohol for over two decades, stopping only three months prior to admission. Recently, he experienced progressive abdominal swelling, early satiety, breathlessness, jaundice, and leg edema, prompting hospital admission. His background of chronic alcohol intake, viral hepatitis, and poor follow-up significantly increase his risk for cirrhosis and related complications.

Subjective Data: Mr. K. complains of difficulty breathing, abdominal discomfort, reduced appetite, fatigue, and occasional confusion. He also reports inability to perform daily tasks due to weakness and swelling.

Objective Data: On assessment, Mr. K. appears cachectic, jaundiced, weak, and disoriented at times. His abdomen is distended with shifting dullness, consistent with ascites. Bilateral pedal edema is present. Vital signs reveal BP: 150/90 mmHg, HR: 96 bpm, RR: 22 breaths/min, Temp: 37.8°C, SpO₂: 92% on room air.

Diagnostic Findings:

- Ultrasound abdomen: Moderate ascites, hepatomegaly with coarse echotexture.

- Liver function tests: Elevated bilirubin, reduced albumin, raised ALT/AST.

- Coagulation profile: Prolonged PT/INR, indicating coagulopathy.

- Renal function: Mildly raised creatinine, showing risk for hepatorenal syndrome.

- Serology: Positive HCV antibodies.

Pathophysiology: Cirrhosis results from chronic liver injury, causing fibrosis and impaired blood flow through the liver. This leads to portal hypertension, forcing plasma into the peritoneal cavity, producing ascites. Simultaneously, low albumin levels reduce oncotic pressure, promoting edema. The retained sodium and water due to impaired renal regulation further contribute to fluid volume excess.

Risk Factors:

- Age (58 years) → decreased physiological reserve.

- Alcohol use → long-standing hepatic insult.

- Hepatitis C infection → chronic viral injury.

- Hypertension and sedentary lifestyle → comorbid burden.

- Recent immobility and poor nutrition → worsened cachexia and edema.

Together, these findings confirm the nursing diagnosis of Fluid Volume Excess related to impaired liver function and portal hypertension, evidenced by ascites, peripheral edema, and breathlessness. The assessment highlights the need for targeted interventions addressing fluid balance, respiratory comfort, and prevention of further complications.

Excess Fluid Volume Nursing Diagnosis

Excess Fluid Volume related to impaired liver function and portal hypertension as evidenced by abdominal swelling (ascites), bilateral lower extremity edema, and shortness of breath.

According to NANDA-I (2021–2023), Excess Fluid Volume is defined as “increased isotonic fluid retention” and is commonly associated with conditions such as renal failure, heart failure, and liver cirrhosis. In Mr. K.’s case, the impaired liver function due to chronic hepatitis C infection and prolonged alcohol use has led to cirrhosis, characterized by fibrosis, portal hypertension, and decreased albumin production. These pathophysiological changes contribute directly to ascites and edema, hallmark features of fluid volume excess.

The clinical manifestations—progressive abdominal distension, dyspnea, early satiety, peripheral edema, and elevated blood pressure—support the diagnosis. Additionally, objective findings such as reduced serum albumin, hepatomegaly, and prolonged PT/INR further validate fluid imbalance secondary to decompensated cirrhosis.

This diagnosis is prioritized because fluid overload not only compromises Mr. K.’s respiratory function and mobility but also increases his risk for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, and worsening hepatic encephalopathy. Early identification and management of fluid volume excess in liver cirrhosis nursing diagnosis are therefore essential to improving outcomes and maintaining quality of life in patients with advanced liver disease.

Goals and Expected Outcomes

Short-Term Goals (within 48–72 hours):

- Mr. K. will demonstrate reduced abdominal discomfort and improved breathing as evidenced by reporting decreased dyspnea and easier positioning in bed.

- Importance: Relieving respiratory distress enhances oxygenation and patient comfort.

- Mr. K. will maintain stable vital signs and fluid balance as evidenced by daily weight monitoring and strict intake/output records.

- Importance: Provides objective measures of fluid retention and guides interventions.

Long-Term Goals (within 2–4 weeks):

- Mr. K. will exhibit reduction in peripheral edema and ascites as evidenced by decreased abdominal girth and improved mobility.

- Importance: Reflects effective management of portal hypertension and sodium/fluid restriction.

- Mr. K. will verbalize understanding of dietary modifications and lifestyle changes (low-sodium diet, alcohol abstinence, adherence to medications).

- Importance: Enhances self-care and prevents recurrence of fluid overload.

- Mr. K. will remain free from complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, or worsening encephalopathy.

- Importance: Preventing complications improves prognosis and quality of life.

By setting SMART goals—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound—nurses can evaluate progress, guide interventions, and ensure comprehensive care tailored to Mr. K.’s condition.

Excess Fluid Volume Nursing Interventions

1. Assessment Interventions

Action: Monitor and record Mr. K.’s vital signs, daily weights, and intake/output every shift.

Rationale: Tracking fluid status is critical to detect early changes in fluid volume excess. Daily weights are the most reliable indicator of fluid retention, while monitoring intake/output prevents unnoticed accumulation. Evidence shows that consistent monitoring improves accuracy in managing cirrhotic ascites (AACN, 2022).

Action: Assess for abdominal girth and shifting dullness once per day.

Rationale: Measuring abdominal girth provides a simple bedside method to monitor ascites progression. Early recognition of worsening distension allows timely medical interventions, such as adjusting diuretics or scheduling paracentesis.

2. Therapeutic Interventions

Action: Position the patient in semi-Fowler’s or high-Fowler’s position and encourage frequent repositioning (every 2 hours).

Rationale: Upright positioning facilitates lung expansion and reduces the diaphragmatic pressure caused by ascites, thereby easing breathing. Repositioning prevents complications of immobility, such as pressure injuries.

Action: Administer prescribed diuretics (e.g., spironolactone, furosemide) and monitor their effect.

Rationale: Diuretics help mobilize excess sodium and water, reducing ascites and edema. Close observation prevents side effects such as electrolyte imbalance or dehydration, which are common in cirrhotic patients (AASLD, 2021 guidelines).

Action: Restrict dietary sodium intake to 2 g/day and provide small, frequent meals.

Rationale: Sodium restriction is the cornerstone of managing ascites in cirrhosis. Smaller meals prevent discomfort from early satiety and help meet nutritional requirements despite reduced appetite.

3. Monitoring and Interdisciplinary Actions

Action: Collaborate with the healthcare team to schedule paracentesis if ascites becomes tense or compromises breathing.

Rationale: Paracentesis provides rapid relief of symptoms and improves respiratory status in patients with refractory ascites. Nursing support is essential for pre- and post-procedure monitoring to prevent hypovolemia or infection.

Action: Monitor for complications such as confusion, decreased urine output, fever, or bleeding tendencies.

Rationale: Cirrhotic patients are at risk for hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and coagulopathy. Early recognition improves outcomes and prevents progression to life-threatening states.

4. Patient Education

Action: Educate Mr. K. and his spouse about alcohol abstinence, medication adherence, low-sodium diet, and daily weight checks at home.

Rationale: Long-term management of fluid volume excess in cirrhosis requires lifestyle changes and self-monitoring. Patient and family education fosters adherence and reduces hospital readmissions.

Action: Teach warning signs requiring medical attention (e.g., rapid weight gain, increasing abdominal distension, confusion, black stools).

Rationale: Empowering the patient to recognize danger signs encourages prompt healthcare seeking, reducing complications and mortality (WHO, 2020 cirrhosis care recommendations).

By combining assessment, therapeutic interventions, interdisciplinary care, and education, nurses can holistically manage fluid volume excess in liver cirrhosis nursing diagnosis. These evidence-based strategies not only relieve current symptoms but also prevent long-term complications.

Evaluation of the Care Plan in Cirrhotic Patients

After implementing the care plan, several goals for Mr. K. were evaluated. In the short term, his breathing improved with semi-Fowler’s positioning, and daily weights showed stabilization at 72 kg, indicating partial fluid control—these goals were met. Strict intake/output monitoring revealed mild positive balance, suggesting that diuretics were effective but required ongoing adjustment—partially met.

In the long term, Mr. K. demonstrated reduced leg edema and reported less abdominal discomfort, though abdominal girth measurements remained elevated, reflecting only partial achievement. He and his spouse verbalized understanding of sodium restriction, daily weight checks, and alcohol abstinence—met.

However, confusion episodes persisted intermittently, indicating incomplete control of hepatic encephalopathy. For this reason, continued monitoring, medication adjustment, and further patient/family teaching were recommended to strengthen long-term outcomes.

Nursing Rationale and Clinical Reflection

This nursing care plan was essential for Mr. K. because excess fluid volume in cirrhosis not only impacts comfort but directly threatens respiratory and cardiovascular function. By applying the nursing process, a structured approach allowed prioritization of interventions that relieved symptoms and prevented deterioration. The combination of monitoring, diuretics, dietary changes, and education provided both immediate relief and long-term strategies for self-management.

One of the main challenges was balancing fluid removal with the risk of electrolyte imbalance and worsening renal function. Despite adherence to sodium restriction and diuretic therapy, Mr. K. still experienced fluctuating ascites, reflecting the progressive nature of decompensated cirrhosis. Another challenge was addressing intermittent confusion episodes, which limited his ability to participate in care decisions and required additional family involvement.

On reflection, earlier involvement of a multidisciplinary team (nutritionists, hepatologists, mental health specialists) could have further strengthened the plan. In future cases, I would also incorporate more patient-centered teaching aids to reinforce dietary and medication adherence, particularly since cirrhosis management requires long-term commitment.

Ultimately, this care plan highlighted the importance of evidence-based, individualized nursing care in managing complex conditions like liver cirrhosis. It reinforced the nurse’s role in not only alleviating physical symptoms but also in empowering patients and families to participate actively in ongoing care.